I confess I am not a great fan of auto-biographies that begin at the beginning and follow a temporal path up to the present day – not that the person might not have some interesting stories, facts and opinions strung on their necklace but it just doesn’t appeal as a structure. On the other hand, in my last, extra year at school in Oxford, retaking an A-level and adding a couple more, I was allowed out of school on my recognisance and saw a fascinating Exhibition at the Modern Art Gallery. The Artist had laid out and photographed every single possession of a single person – for example, all the cutlery was laid out in one shot, all the shoes in another. This more thematic approach appeals more and although I am not arranging the objects which I have chosen to tell my story in chronological order, I hope that my writing will be sufficiently interesting to keep your interest Dear Reader, and that on the journey from A to Z, you will assemble an impression of my life and who I am…

If you have ever received a comment from me on WordPress, you may have wondered about my username Frewin55 – short story, Frewin is my middle name and 1955 the year I was born and so I turned 70 just last month. The more interesting and turbulent story of why I was named Frewin is told in a recent poetry post I made for dVerse Poets Pub – Whats in a Name.

Fossils

Fossils and thus Geology, are another interest that I got from my mother. We used to holiday in Charmouth, Dorset – part of what is now (since Jurassic Park popularised dinosaurs) called The Jurassic Coast although the same feature occurs in East Yorkshire where the same rocks appear having snaked their way up through the geology of England. I wrote about my mother, Charmouth and fossils in a poem called Cast in Gold here,

In the picture (top row from left) you can make out a Turritella in a cross-section, a section of a bed of bivalve fossils, a colonial coral from the Middle Carboniferous at Rathlee, Ireland where we used to live, ditto the one below. Left hand column – Various Ammonite fragments from Charmouth, the top one is made from Iron Pyrites – Fool’s Gold. Second column – a “Devil’s Toenail from Runswick Bay, East Yorkshire and below, two fragments of Crinoid beds. Third Column, the two white fossils are coral that my stepson brought back from Mexico – they are much closer to modern corals than the Carboniferous examples. Below them, three Rhynconella fossils which by corrugating their shell shape, could maximise their intake of water to filter for food whilst only opening a tiny amount and thus keeping safe from predators. Fourth column, Belumnites so called because of their resemblance to bullets – from Charmouth, just this year when I introduced my partner to the joys of fossil hunting. Bottom right, a recent (geologically speaking) piece of Bog Oak – a very fragile piece of wood preserved in the bog that formed when the climate became much wetter five thousand years ago – first drowning the trees and then growing five feet of peat bog to bury and preserve the base of the trees. Five thousand years is a mere moment in geological time and it is unlikely that the bogs and bog oaks will survive as fossils in the long term – most likely, the current climate change will stop the process of peat bog formation and the bogs and their fossilised trees will be eroded away…

Film

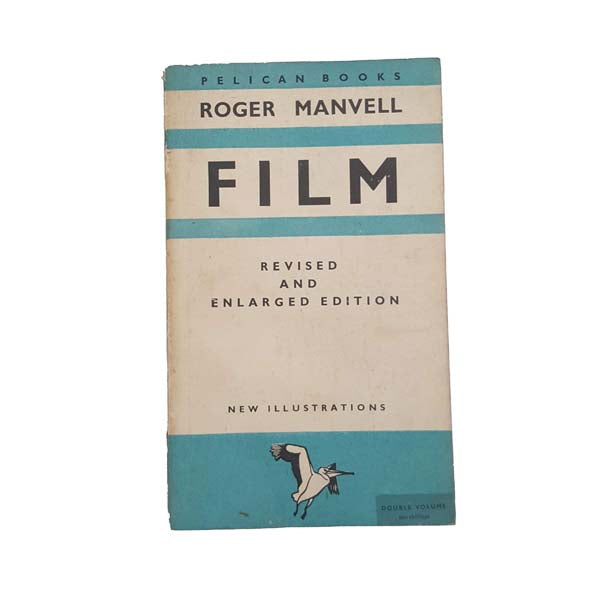

My love of Film began with a book -a Pelican, from the publishers Penguin and like all Penguin books, Film, by Roger Manvell, wore the “utility” style cover from the immediate postwar period which became so iconic. My father had a little bookcase exclusively full of these Penguin and Pelican books which I guess he had bought before he married my mother. “Film” contained sections of B/W stills from films such as Battleship Potemkin (the woman shot in the eye on the Odessa Steps), Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or (the eye and the razor-blade) and The Seventh Seal – all images so intriguing that they lit a fire in my young brain even though it would be years before I would have a chance of seeing these films.

When I first dipped into this book, we didn’t even have a TV and when we did, the only films shown were in my father’s words “American rubbish” and it would not be until I lived in London, post-university, and got a job at the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton, that I finally saw some of these “arthouse” movies. I started as a general helper, selling tickets, ushering, clearing up between films and serving cakes, quiche and coffee but not sweets and popcorn – an innovation in Cinema fare for those days. The Ritzy showed at least 10 different films over the course of a week and since it had a single projector, that meant the projectionist had to combine an average of seven “cans” of film into one large and heavy reel – cutting off the header and footer from each can’s contents and splicing the sections together and then reversing the process when the film was finished with. This was so much work for the projectionist, one of three founding members of the cinema, that when I asked if I could help (nothing venture nothing gain) he jumped at the chance. I can truly say that this was one of the most enjoyable jobs I have ever had and by the measure that when you find something you love, it doesn’t feel like work.

Nowadays, cinemas, even small ones, have digital projectors and cans of film are a thing of the past and many great works are to be found on streaming services so much of the romance of the physical cinema has been lost for most people, the lights going down, the audience hushing, the ads, the previews and finally the film itself…There is one thing which is particularly magical about a real film projector and which only projectionists get to see… You can open the “gate” which is where the film passes through the beam of light which projects it onto the screen. To create the illusion that our eyes and brains see as moving images, it is necessary that the projection is broken up into individually illuminated frames, so when you open the gate, the synchronised flashes of light illuminating the fast-moving film, make it appear that the film is stationary, that is magical enough, but look more closely at the frames in the gate and you can see the characters moving in miniature just as they are doing on the cinema screen…